In September 1897, the strange story of Emily Raynor mesmerised the British public. It was a tale of sinister men in black, hypnotism, abduction and an innocent girl who narrowly avoided a life of slavery in an Ottoman bordello…

The Lady Vanishes

Emily Raynor (19) was the daughter of a doctor and a nurse from Bishop Aukland, and was described as of ‘extremely prepossessing appearance and manners’.[i] On Friday 17 September 1897 she moved to Leamington to take up the position of governess to the children of Mr and Mrs Cowper. The following Monday, Emily, wearing a blue serge dress and dark straw hat, set out to post a letter to her mother saying that she was very happy in her new position. She did not come back.[ii]

Her employers searched for her and contacted the police when they realised Emily was missing, though no sign of her could be found. The Cowpers were relieved, though, when the following day they received a telegram saying Emily had been found in London. She was soon reunited with her mother and told the police a remarkable story that gripped the whole country.

The Men in Black

Emily recounted how on the morning of her disappearance, she had been picking flowers in the garden when two men approached her. One of them said ‘Good morning!’ to her over the hedge, but she ignored them. They were dressed in black with tall black top hats, and one of the men had particularly ‘ferrety’ eyes.[iii]

Later she went out to post the letter to her mother, and was again accosted by the two sinister black-clad strangers. One of these touched her on the back of the neck with his finger and she swooned and lost consciousness. She had a vague impression of being driven somewhere in a horse-drawn cab, but the next time she became fully conscious, she was surprised to find that she was in a first class train carriage. Sitting opposite her, to her horror, were the two men in black. One of the men, presumably the one with the ferrety eyes, reached over and touched her again and everything immediately went black.

The next time she became conscious, the strangers were shuffling her through the London streets. She took this opportunity to escape her captors and threw herself into the arms of a passing elderly gentleman, begging for his protection. The sinister strangers disappeared into the London streets.[iv]

The man escorted Emily to Macready House Theatrical Mission on Henrietta Street. This mission was opened in 1885 and was run by evangelical Christians as a club for young women who worked in the theatre to provide a safe place for them between rehearsals and performances – young actresses were seen as being in grave moral danger.[v]

The Mission contacted Emily’s mother, and the girl told her remarkable story. It also turned out that her money and jewellery had been stolen, presumably by the sinister men when she was unconscious in what appeared to be a hypnotic trance.

Indeed, when her employer Mrs Cowper next met Emily, she said that Emily appeared dazed as if recovering from some kind of hypnotic sleep. Mrs Cowper told the press that she believed that the men in black were trying to abscond abroad with the ‘young and innocent girl’ for improper purposes.[vi] This interpretation was confirmed, according to the press, when Emily’s mother was told by Scotland Yard authorities of a similar case that occurred a few days earlier. They believed that an underground gang were attempting to abduct young girls and smuggle them to Constantinople, where a dismal fate awaited them.[vii]

See Emily Play

The police investigations into Emily’s story were revealing. They could not trace any cab driver who had taken an unconscious girl and two suspicious men in black to Leamington station, but a railway official had seen Emily. He saw her pass the ticket gate and enter a third class carriage of the London train – alone.[viii]

Even stranger, investigations showed that Emily had visited a Leamington jeweller’s shop where she had sold some items at 2.30 pm on the day she had dissappeared. This was after her alleged abduction by the ferrety eyed hypnotist.[ix]

Emily, it seems, had stars in her eyes and dreamed of a career on the stage, but her mother disapproved. The girl had sold her jewellery and then bought a train ticket to London, where she heard that a theatrical agent in Henrietta Street was offering board and lodgings as well as training to aspiring actresses. She wandered round Henrietta Street looking for this agent, and eventually found a Mr Denton, who immediately escorted her to Macready House Mission and asked the superintendent there to take care of her and contact her family and friends.[x]

Although Emily stayed at the Mission all day Tuesday, she made no mention of being hypnotised or abducted. Only when she was told that her mother was coming to collect her did she confide her exciting adventure and desperate escape from sex slavery.[xi]

Contrary to previous reports, it seems the police had never believed her abduction tale.[xii]

Emily Borrows Somebody’s Dreams

Emily had run away to join the theatre and then concocted her melodramatic adventures with ferrety-eyed hypnotists in black to keep her escapade from her mother. The newspapers, though, could not but help admire the girl’s imagination. She ‘ought to be a journalist or an author of melodrama,’ said one local newspaper. ‘She has imagination, grip, insight. She knows a good story when she sees it.’[xiii]

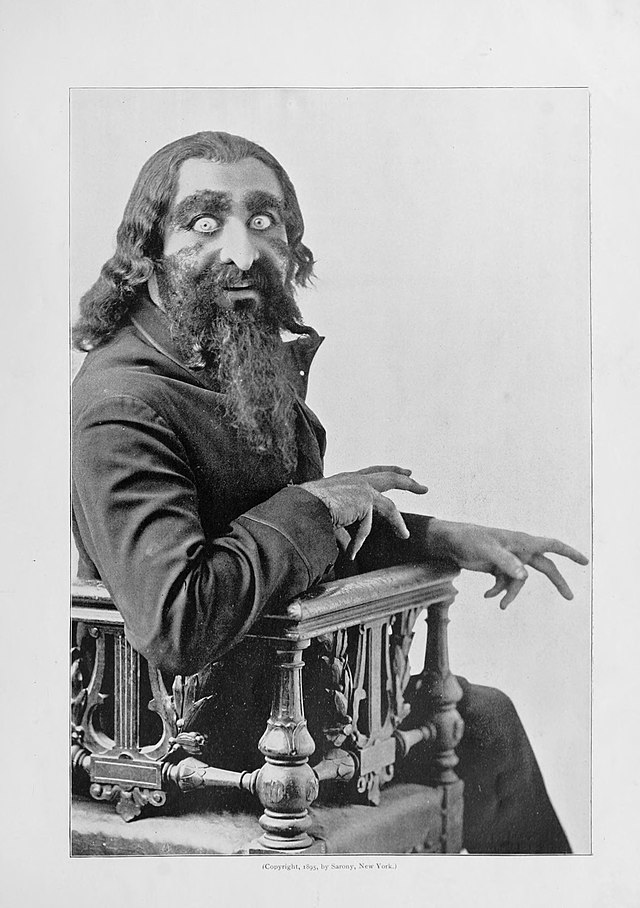

Emily’s tale reflects a number of themes that would have been prominent in the public mind at the time. Certainly hypnosis had started being used as a plot device in sensationalist fiction such as the Moonstone by Wilkie Collins (1868) and George Du Maurier’s bestseller Trilby (1895). Trilby tells the story of how a beautiful tone deaf Parisian woman named Trilby is hypnotised, seduced and exploited by Svengali who turns her into a hugely successful opera singer without her being aware of it. The character of Svengali gave his name to anyone who dominates and manipulates those around him with his hypnotic personality. The novel became a hit stage play, and it seems that Emily’s story owes something to these Victorian melodramas.

The fear that women might be abducted and sold into prostitution was another concern that helped make Emily’s story attractive to the media. This would have seemed plausible in the light of W.T. Stead sensational series of articles on child prostitution ‘The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon’[xiv] published in 1885.

However, hypnotism is not an effective means of abducting one’s victim and belongs purely in the realm of fiction. It was this imaginary flourish that ultimately made Emily’s account implausible. As with cases of alien abduction or Satanic Ritual Abuse, if hypnotism is part of the story, great scepticism is required.

Epilogue

Presumably Emily’s dreams of a glamorous showbusiness career went unfulfilled, though she certainly was centre stage in her own exciting melodrama.

Ironically, as one newspaper noted: ‘So much publicity, however, has been given to the affair that there are probably plenty of theatrical managers who would now be only too pleased to secure her services.’[xv]

For another strange abduction hoax with a Halifax connection, see here: The Mystery of the Bound and Gagged Girl

Stay tuned for more forgotten tales of imaginary abductions that put the ‘kid’ in kidnap…

[i] ‘Alleged Abduction in Leamington’, Leamington Spa Courier, 25 September 1897, p.5

[ii] ‘The Strange Story Explained’, Shields Daily Gazette, 25 September 1897, p.3

[iii] ‘Extraordinary Story by a London Governess’, Leamington, Warwick, Kenilworth and District Daily, 24 September 1897, p.3

[iv] Ibid

[v] Kathleen Heasman, Evangelicals in Action: an Appraisal of their Social Work in the Victorian Era, (London: G.Bles, 1962), p.277

[vi] Alleged Abduction in Leamington’, Leamington Spa Courier, 25 September 1897, p.5

[vii] ‘Extraordinary Story by a London Governess’, Leamington, Warwick, Kenilworth and District Daily, 24 September 1897, p.3

[viii] ‘The Strange Story Explained’, Shields Daily Gazette, 25 September 1897, p.3

[ix] ‘The Leamington Governess’s Mysterious Journey to London’, Leamington, Warwick, Kenilworth and District Daily, 25 September 1897, p.3

[x] ‘The Leamington Romance,’ Liverpool Echo, 25 September 1897, p.3

[xi] Ibid

[xii] Ibid

[xiii] ‘Miss Raynor’s Romance’, Witney Gazette and West Oxfordshire Advertiser, 2 October 1897, p.3

[xiv] W. Sydney Robinson, Muckraker: The Scandalous Life and Times of W.T. Stead (London: The Rodson Press, 2013)

[xv] ‘Leamington Romance’, South Wales Echo, 25 September 1897, p.3

One thought on “Kidnapped! The Amazing Adventure of Emily Raynor”