Christmas Horror from 1734

If you thought the tradition of the Christmas ghost story started with Charles Dickens, think again. In the eighteenth century many people’s Christmas reading list would have included a best-selling little pamphlet called Round About Our Coal Fire: Christmas Entertainments. It was written by an anonymous author who called himself Jack Merryman, and featured articles about seasonal games and traditions, ribald jokes and stories including the first known version of ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’ – or ‘The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean’ as it was originally known.

However, the pamphlet also included chapters about ‘fiddle-faddle stuff’ – in other words, ‘Fairies, Ghosts, Hobgoblins, Witches, Bull-beggars, Rawheads and Bloody Bones’.[i]

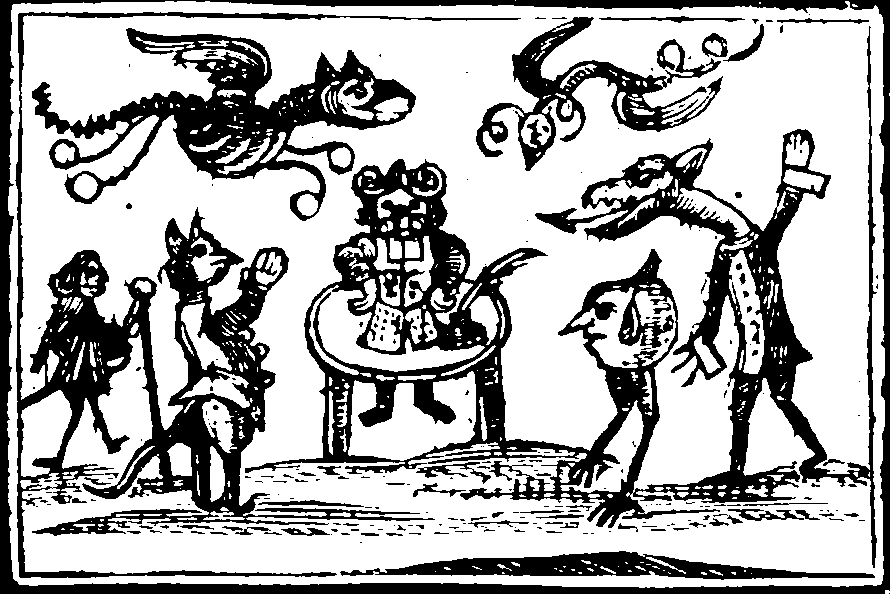

Bull-beggars, Rawheads and Bloody Bones are various kinds of unpleasant fairies, hobgoblins or bogey men. The wood cut at the top of this article from Round About Our Coal Fire gives you an idea what they look like…

These scary legends and stories in the pamphlet were told for fun, and as an excuse for young couples to cling tightly to one another in the dark midwinter, though some of these supposedly true tales seem very odd to modern sensibilities.

One of the ghostly accounts in the pamphlet is interesting because its depiction of a ghost is as far removed from the stately Victorian apparition as could be, and it also answers the burning question of why is a ghost like a fart?

The Ghost of Mr Thomas Stringer

Mr Thomas Stringer was a successful young gentleman with a promising future before him. What’s more, he had courted and won the heart of a great beauty and they pledged eternal love by bending a piece of gold between them. However, after they married, the young woman still attracted streams of admirers, and eventually fell for one of them.

Mr Stringer found out and confronted his wife about her infidelity, though she simply replied that she would do as she wished.

Her distraught husband poisoned himself, leaving his wife free to be with her lover.

One night as she lay in bed with her new man, an eerie red glow appeared in her bed chamber. Thomas Stringer had returned from the grave. His hair was made of serpents and his hands and feet were eagle’s talons. The spirit crawled along the floor like a toad croaking hideously all the while, his glaring eyes fixed on his faithless wife. He appeared red hot as the unearthly crimson glow surrounded him.

Mrs Stringer attempted to wake her fancy man, but couldn’t. The toad shaped creature crawled up onto the bed and kissed his wife with his ugly mouth before spitting venom in her face and saying in a loathsome voice: ‘Now I have caught the faithless Bitch, Damn your Blood!’

Then with his iron claws he tore her to pieces and sent the scraps to the devil.

And all the while the candle burned blue.

Corpse Candles

The candle burning blue alludes to the ghostlore of centuries past when spirits were often thought to take the form of luminescent blue flames. Sometimes these ghostly glows were called corpse candles or death lights. At the moment someone died these bluish flames would leave the house and traverse the path along which the funeral procession was to follow to the church. The corpse candle would then pass into the church where the coffin was to be taken and light up the whole building with brilliant blue light before proceeding to the grave that was soon to be the deceased’s final resting place.[ii] When the light burns blue, it’s as if a portal opens between our world and another.

That’s why on the eve of his death at the battle of Bosworth, Shakespeare has King Richard III say:

The lights burn blue; it is now dead night.

Cold fearful drops stand on my trembling flesh

This was when the ghosts of the people Richard destroyed on his bloody rise to the top came back to haunt him.

And this is why Dick Merryman decided to end his ghostly story like this, which sounds like it came straight out of a Georgian Christmas cracker: ‘A Ghost and a Fart are the same Thing, for a Fart will make the Candle burn Blue as well a Ghost…’

[i] Jack Merryman, Round About Our Coal Fire, or Christmas Entertainments. (J. Roberts, 1734). It’s easy to find online.

[ii] Owen Davies, The Haunted: A Social History of Ghosts (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), p.18

One thought on “Why is a Ghost Like a Fart?”