On 21 February 1970, pianist Peter Evans sat at a piano in Watter’s Gallery, Sydney and prepared himself for a performance of French composer Erik Satie’s 1893 composition Vexations. The piece is notorious for its weird intervals and disturbing effects on both the performer and audience… and the fact that Satie gave instructions that the motif should be repeated 840 times. Depending on the speed it’s played, that’s a performance lasting somewhere between 18 and 24 hours.

Evans started well, performing the unsettling and repetitious melody, but things started to go wrong as he approached repetition number 595. He felt his mind fill with evil thoughts, and he saw animals and ‘things’ peering at him through the musical score.

‘I would not play this piece again’, he said. ‘I felt each repetition slowly wearing my mind away. I had to stop. If I hadn’t stopped I’d be a very different person today… People who play it do so at their own great peril.’

Another pianist called Linda Wilson took up the challenge when Evans abruptly stopped and played the remaining 245 repetitions without any ill effects.[i]

Cats on a Piano

I first became aware of Satie’s weird composition when I accidentally tuned in to an all-night performance of it on BBC Radio 3 in 2006. I’d been looking for some soothing music to help me drift off to sleep, rather than something that would cast its disturbing shadow over my dreams. When I awoke the next morning, it was still playing.

The score for the piece includes an enigmatic note from Satie saying ‘To play this motif 840 times in succession, it would be advisable to prepare oneself beforehand in the deepest silence, by serious immobilities.’

The score consists of a short single line melody. This seemingly directionless tune is then repeated but harmonised with mostly diminished chords. Then the theme is played again without the harmony. Finally, the tune is repeated with the same harmonised chords, though in different inversions. This cycle lasts about a minute. And then, repeat 840 times…

But Satie wanted to keep any performers on their toes. His notation is eccentric with liberal use of double flats and scoring the B as a flattened C. The pianist has to really concentrate – it’s so unnerving and confusingly notated that it’s impossible to get used to it. As you can imagine, after a few repetitions, the confusing sharp, flat and natural symbols all begin to blur into one another.

You can hear a few minutes of it here.

To me Vexations sounds like a cat gingerly plodding over the piano keyboard, followed by two cats gingerly plodding over the piano keyboard in unison. However, some scholars think the weird melody includes arcane numerological and esoteric references, something that Satie was interested in.[ii]

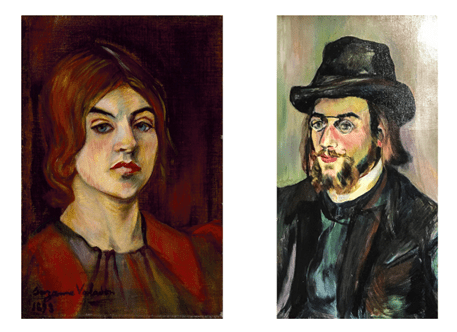

It’s quite possible that Satie was expressing his feelings about his short and stormy relationship with artist Suzanne Valadon.[iii] In any case, the melody and harmonies feel dissonant and unresolved, whatever the obscure cabalistic or numerological significance hidden in the piece.

It was often assumed that Vexations would be nigh on impossible to perform. However, musicians around the world cried, ‘Hold my beer…’

Hold My Beer

One contender for the first full performance was given by Richard David Hames in 1958, who remarkably was only a 13 year old school boy at the time. It took place at Lewes Grammar School in Sussex and raised £24 for charity, though this claim to the first performance hasn’t really been confirmed.[iv]

Probably the best known confirmed early performance was organised by avant-garde composer John Cage, famed for his composition 4.33 in which the pianist sits in silence at the piano for four minutes and thirty-three seconds. Cage used a team of 10 pianists to perform Vexations in the Pocket Theatre, New York in 1963. The performance took nearly nineteen hours.[v]

She Loved Nudity

Cage organised another performance in Berlin in 1966, this time involving a relay team of six pianists. One of these, Charlotte Moorman performed her parts with her boobs out because, well, it was the swinging sixties after all. Moorman was known as the Topless Cellist for her habit of performing in a state of undress, though sometimes on televised performances she would play cello while wearing a bra made of two mini televisions.

Moorman said she performed her parts of Vexations topless because she ‘loved nudity’, but it also seems John Cage had bet her $100 that she wouldn’t do it. She won the bet.[vi]

A phial of amphetamine

The first confirmed solo performance was by Richard Toop in 1967 at the Arts Lab, Drury Lane, London. Toop used 840 numbered copies of the score so that he could avoid the danger of losing count. After around sixteen hours, Toop was flagging and asked for some extra stimulant in his coffee, expecting a vitamin pill. Instead, as he found out later, he was dosed with a phial of amphetamine. ‘The effect was hair-raising’, he said. ‘My drooping eyelids rolled up like in a Tom and Jerry cartoon.’ No wonder some newspaper reports commented on the performer’s glazed expression…

The performance took 24 hours, and Toop noted that even after playing the piece for so long and so many times, he still couldn’t play it from memory.[vii]

The same feeling Frankenstein must have had

Another notable performance of Satie’s piece was by Gavin Bryars and Christopher Hobbs in Leicester Polytechnic in 1971. The two pianists took it in turns to play, and while on breaks between shifts wrote each other notes to be read when they changed places. This gives a fascinating insight into what it’s like to be one of the performers.

As he played, one of the performers had the unnerving impression that there was someone standing behind him, though at that early stage in the performance, the only other person in the room was the caretaker, and he was sweeping the floor.

‘When I make a mistake’, the other wrote, ‘it’s like the end of the world. The music is unnerving because it’s impossible to get used to it – the unexpected keeps happening.’

One pianist commented on the difficulty of following the score. The disorientating use of sharps and flats meant that he was never sure he was playing the right notes and that the symbols on the score started to melt into one another. ‘It’s the same feeling Frankenstein must have had,’ he wrote.

The performance was remarkably fast, taking a mere fourteen and a half hours. Perhaps, like Richard Toop, someone had put something in their coffee…

Epilogue

Some have said Satie’s piece is an avant-garde study of boredom and frustration, others suggest it’s the musical equivalent of a zen koan. Scholars have discussed the esoteric significance of the disturbing harmonies and tangled numerological meaning hidden in its off-kilter progressions or the occult magical properties of the number 840.

But the fact is that there’s no indication Satie ever thought of having the piece published let alone performed. It’s been suggested that Satie’s comment about playing the piece 840 times is not actually an instruction, but more a kind of note to self: If you wanted to play the piece 840 times, it would require careful psychological preparation and meditation – which is perhaps what Satie meant by ‘serious immobilities’.[viii]

Could he simply have been having a joke?

I picked up a vinyl copy of a performance (pictured below). It has twenty cycles on each side, so that’s forty altogether. To listen to the equivalent of a ‘full’ performance, I’d have to play both sides of the record 21 times. I’m afraid I can barely get past the first few minutes…

For more weird musical history:

[i] Gavin Bryars (1983) ‘Vexations and its performers’, Contact: Journal for Contemporary Music, 26, pp.12-20 (p.13)

[ii] Robert Orledge (1988) ‘Understanding Satie’s ‘Vexations’’, Music & Letters, 79(3) pp. 386-395. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/855366

[iii] Ibid p.390

[iv] Bryars (1983) p.13

[v] Ibid

[vi] Ibid

[vii] Ibid

[viii] Steven M Whiting (2010) ‘Serious Immobilities: Musings on Satie’s “Vexations”’, Archiv für Musikwissenschaft, 67(4) pp. 310-317