In January 1726 the British ships the Compton and the James and Mary anchored off a desolate uninhabited island in the South Atlantic for repairs. Men were sent ashore to find provisions, but instead came across a tent with a man’s skeleton lying near it. Next to the skeleton was a manuscript – a diary of the dead man’s last days as a castaway on this remote island. The diary was written in Dutch and told a horrifying tale of a man haunted by madness and despair and plagued by monstrous demons…

The Castaway

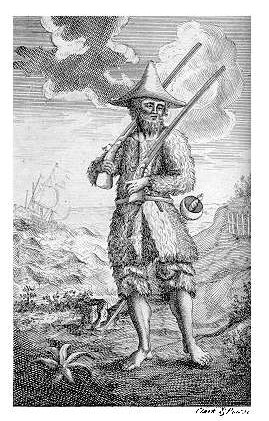

In May 1725 Leendert Hassenboch, a 30-year-old Dutch sailor was put ashore on Ascension Island as punishment for ‘sodomy’, a crime considered worthy of the death penalty at the time. He had some clothes, a cask of water, some rice, two buckets, a frying pan and a tent which he pitched near the shore.

Ascension Island measures 37 square miles and is situated in the South Atlantic, about halfway between Africa and South America. When Hassenboch was abandoned there, it was uninhabited, dry and barren. Vegetation was sparse but food was available in the form of easy to catch seabirds known as a boobies, as well as turtles and goats. What was hard to find was fresh water.

Hassenboch made good use of the boobies and the turtles when he found them, but his searches for fresh water were fruitless. Within a month, his water was gone. And he was mad with thirst.

This is where Hassenboch’s diary, which has been fairly matter-of-fact up to this point, becomes ever more horrific.

The Devils Break Out of Hell

On the evening of the 16 June, Hassenboch heard voices cursing, swearing and blaspheming. He was, of course, alone on the island. This is his diary entry:

It seemed to me as tho’ all the devils had broke out of Hell. I was certain there was no man on the island but myself, and yet I felt myself pulled by the nose, cheeks, &c and beat all over my body and face… they tormented me without ceasing in this manner for several hours.

His ordeal continued on the night of 20 June. He wrote:

This night I was again miserable tormented and beaten by these devilish spirits, so that in the morning I thought all my joints were broken. There was likewise the same hellish and blasphemous noise as before…

On the same night Hassenboch wrote that he was visited by Andrew Marsserven, a debauched person he had known when they were both soldiers. Tormented by guilt at his sodomy, Hassenboch wrote of this vision of the man from his past:

I have heard him use the most blasphemous expressions that can be. I have likewise with my eyes seen a great many imps of hell; and I must also say this for a warning to the reader, that to my great sorrow now. I was a sodomite, of which I am now too sensible; for he follows me everywhere and will not let me be quiet.

Hassenboch spent the next few miserable weeks searching vainly for water and watching for ships that never came. On 1st July he wrote: ‘The water is dried up everywhere and I am almost dead with thirst.’

By 21 August Hassenboch could see only one solution to keep himself alive. He wrote on 21 August:

This day I began to drink my own urine, to try if I could bear it on my stomach. The reader may imagine to how miserable circumstances I was reduced on this desolate island, since necessity obliged me to try this method.

His stomach could not bear it. Nor could it bear the turtle blood and urine from a slaughtered turtle’s bladder that he also drank. He frequently vomited up whatever liquid he managed to take.

On 30 August Hassenboch climbed a small hill to look for any signs of water, but could see nothing. He began to despair:

My great misery gave me thoughts of killing myself; but thanks to God I at last got safe down, though I frequently fell by the way through weakness.

His evenings were grim indeed:

When the moon rose I went for eggs, and found here and there a bird, the heads I cut off and sucked of the blood. Going back to my tent, I talked to the dead stinking turtle like a man besides himself, and as I was going to my grave. I then drank a whole bottle of urine, and laid down…

As he grew weaker, the diary entries became less frequent and shorter. They tell of eating raw eggs, raw flesh and drinking his own urine.

The last entry on 14 October read simply ‘I lived as before’.

A True Relation of Sodomy Punished?

After the British mariners found Hassenboch’s camp and diary, they took it back to London where it was translated into English and published in 1726 under the title of Sodomy Punish’d and then again in 1728 titled An Authentic Relation of the Many Hardships and Sufferings of a Dutch Sailor. A third version was published in 1730 called The Just Vengeance of Heaven Exemplifyed.

Dutch historian Michiel Koolbergen discovered from researching shipping logs that Hassenboch was indeed a real person. He had been bookkeeper aboard the Prattenburg and was returning from Cape Town when he was sentenced to be abandoned on a deserted island for committing sodomy. The severity of the punishment was consistent with the times. Dutch sailors convicted of sexual relations with one another were often tied together and thrown overboard.

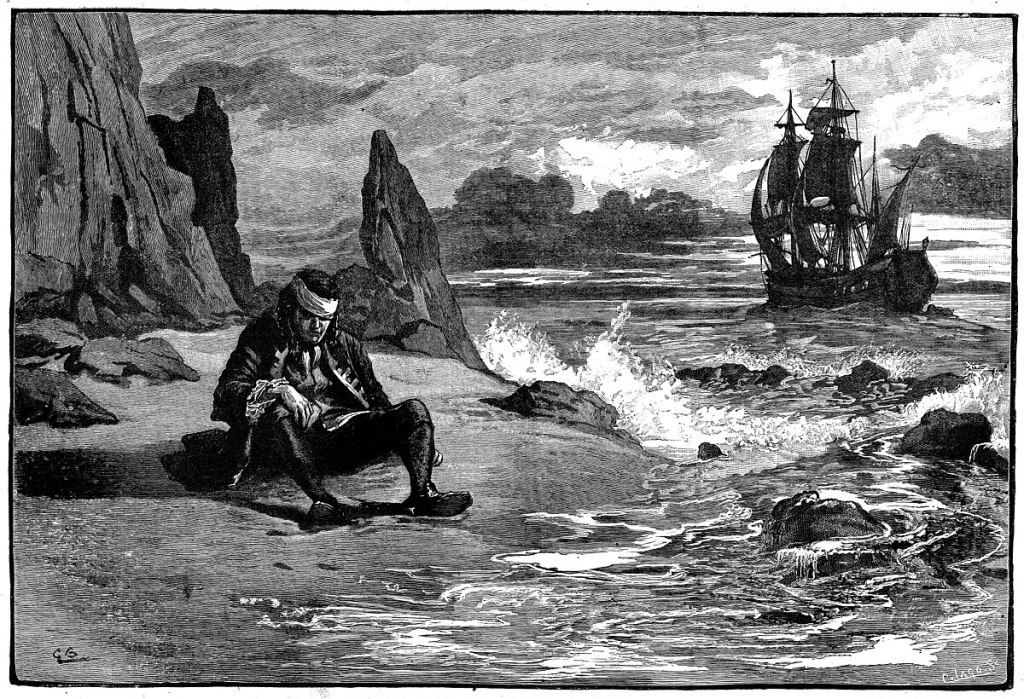

Koolbergen also consulted the ships logs for the Compton and the James and Mary, and they did indeed find Hassenboch’s camp and diary on Ascension Island. The skeleton, however, was a macabre and fanciful addition to the 1730 version on the diary. The ships logs note that they could find no sign of Hassenboch’s remains.

Diabolical Inventions

It would be nice to think that because his remains were not found, Hassenboch was rescued by a passing ship. Unfortunately, this seems unlikely – it would surely have been reported if he had been saved. Reports of castaways being rescued were popular – this was the era of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, which was published a few years prior in 1719.

It’s likely that Hassenboch either died of thirst or took his own life. It could be no body was found because he died on another part of the island, or it could be that his remains were washed away by the waves. Perhaps he threw himself into the sea to end his agonies.

Some of the most striking parts of Hassenboch’s diary are the sections where he feels himself to be mentally and physically tormented by demons and spirits. However, historians who’ve studied this story (such as Michiel Koolbergen and Alex Ritsema) suggest that these lurid passages, along with the ones where he laments being a sodomite, were added by the publishers to make the diary more exciting. The use of literary devices (such as addressing the reader) in these passages is suspicious. It’s not as if Hassenboch was intending his manuscript to be published.

Some historians have noted the similarities between the more haunted entries in Hassenboch’s diaries and episodes in Robinson Crusoe. The original diary (which was in Dutch) is lost, so it’s impossible to know how much of the diary was faked, but it seems likely the more sensationalist entries were fabricated by the publishers.

The 1726 and 1728 versions of the diary end abruptly on 14 August 1725. The 1730 edition of the diary ends on 14 September, and finishes with a different final entry, clearly made up by the publisher to give the story a sense of an ending by having poor Hassenboch die mid-sentence:

I cannot write much longer: I sincerely repent of the sins I committed and pray, henceforth, no Man may ever merit the Misery which I have undergone. For the Sake of which, leaving this Narrative behind me to deter Mankind from following Diabolical Inventions. I now resign my Soul to him that gave it, hoping for Mercy in –…

The various publishers of Hassenboch’s diary just could not leave him alone. They couldn’t resist sententious moralising by attributing spurious confessions and lamentations of his sin to the text. Nor, could they resist adding some imps, demons and spirits to haunt Hassenboch’s last days – a bit of sensationalist horror would certainly be good for sales.

And the publishers felt the need to bring the narrative to a more satisfying ending, fabricating an entry where the castaway dies melodramatically mid-sentence. All that was needed to complete the story was a more dramatic beginning provided by Hassenboch’s skeleton.

FINIS

References

The full text of Sodomy Punish’d is available online

The most thorough examination of this episode can be found in the following work: Alex Ritsema A Dutch Castaway on Ascension Island 1725 (2010)