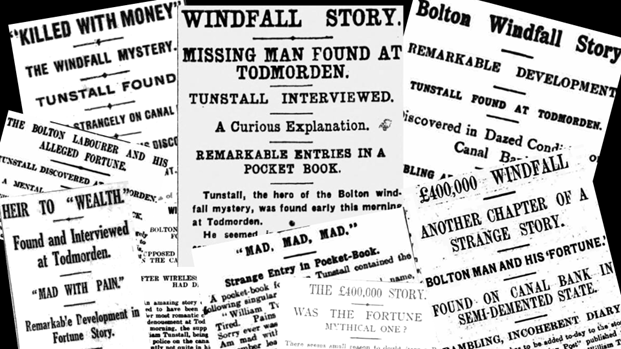

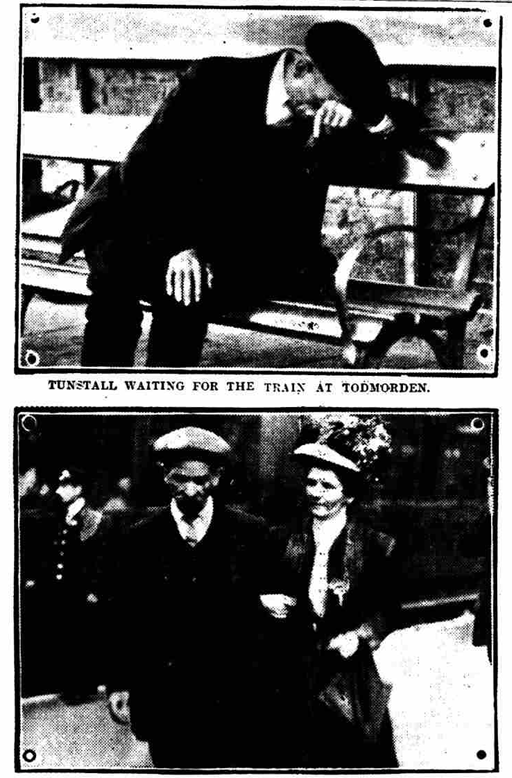

In the early hours of 20 August 1913, PC Machlachlan saw a man behaving in a strange manner on the banks of the Rochdale Canal, in Todmorden, West Yorkshire. The man seemed dazed, confused and dejected and as if he were not in his right mind. The policeman worried that the man was about to throw himself in the canal, so he engaged him in conversation, though the man only rambled incoherently about trouble and pain in his head.

In the man’s pocket was a notebook with some strange messages that gave a clue as to his identity:

William Tunstall; Westwell real name; tired, pains in the head something awful… Mad, mad with pain… Where have I been? God only knows, I don’t… Wish had never known about money… Mad, mad, mad, killed with money… If this is having money I am tired of it. You will find me where you find this. Goodbye and God bless you.

W. Tunstall Westwell[i]

The only thing was, William Tunstall had been reported dead and buried at sea a few days earlier…

The officer took the forlorn Tunstall to the police station, and it became a sensation as news spread around the town. The remarkable story of William Tunstall, how he inherited a fortune but then died mysteriously before he could claim it, had been on everyone’s lips for days. And now here he was, seemingly back from the dead and walking the towpaths of Todmorden.

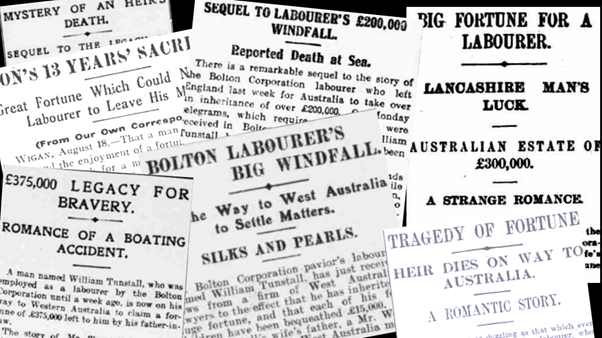

The press called it the Windfall Mystery, but the solution to it was right under their noses all the time.

The Bolton Windfall Mystery

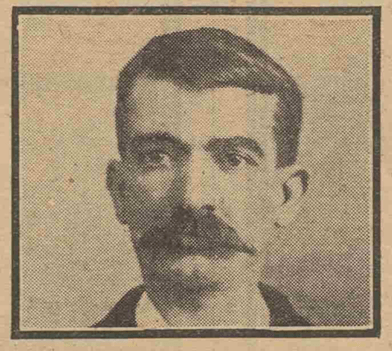

In the summer of 1913, the great feelgood news story was that of middle-aged Bolton man William Tunstall. Tunstall worked for the council laying paving stones and seemed to be somewhat down on his luck, when in true rags-to-riches fashion he received a telegram from Australia. His father-in-law had died leaving him a legacy of around £400,000, which would be close to £60 million in today’s money. His father-in-law, Mr Westwell, had emigrated to Western Australia where he had made a fortune in the silk and pearl fishing industries, and all this along with a huge estate was William’s. The only condition was that he take on his late father-in-law’s surname. With the help of Harry Hart, a friend from Glossop, William planned to join the steamship Omrah to sail to Australia and claim his inheritance.

In a letter sent just before he was due to sail, Tunstall wrote touchingly: “I have had a hard struggle through life with short exception… I have always been true, honest, upright, and attentive to my work.” He was seen as a pious, abstemious and down-to-earth man who attended Bible classes and supported several orphaned children on his meagre income.[ii]

The story of how William came into his fortune was a romantic one indeed. It began when he was on holiday in the Isle of Man and rescued two women after a sailing accident. A pleasure boat was struck by a sudden squall and capsized, and Tunstall being a strong swimmer became the hero of the day. The husband of one of the women Tunstall saved was Mr Westwell, and they became friends.

Some years later William was being treated in hospital for a mystery illness and fell in love with the young nurse who was looking after him. The nurse, though, disappeared and William despaired of ever seeing her again. To help him recover, Mr and Mrs Westwell invited him over to Douglas in the Isle of Man to be their guest for a while. It was there that he finally found the young nurse he had fallen for, and sounding like something from a Mills and Moon love story, she turned out to be the daughter of the Westwells.

A romance blossomed between the two and the young Miss Westwell asked William to marry her, such was the admiration and gratitude she felt for the man who had saved her mother’s life. But William, we are told, was a modest man and painfully aware of the difference in social status between the couple and refused for a time before eventually setting aside his scruples and marrying her in 1900. They had a child together.[iii]

Soon after, Mr and Mrs Westwell decided to move to Australia and insisted their daughter and grandchild go with them, but William declined and stayed at home to look after his ailing mother.

A few months later, William received devastating news – his wife and child had been killed in a carriage accident.

Ten years later William married the woman who had taken over the care of five orphaned children he had been financially supporting.

And now he was a rich man, heir to a silk and pearl fishing fortune. His second wife and the children had moved to the South of France using an advance on his inheritance and he said goodbye to his family, workmates and friends from his Bible class, and headed to London where the steamship Omrah waited to take him to his fate. His biggest fear, we are told, was that news of his fortune would leak out making him famous, in which case he would have to ‘disappear suddenly’, as he said ominously.[iv]

Shortly after the Omrah had set sail, Tunstall’s brother John received a terse telegram: Sorry, your brother dead: buried. Myself am going to Canada.[v]

Tunstall’s landlord received a similar message: Sorry Tunstall dead; buried. Tell friends.[vi]

The laconic telegrams were unsigned, but it seemed likely that it had been sent by Harry Hart, the man who was organising William’s passage to Australia. The mysterious death of the windfall man was a media sensation that seemed straight out of the pages of a Sherlock Holmes mystery…

The Plot Thickens

As journalists began to investigate the suspicious death of William Tunstall, the whole story began to unravel. Reporters from the Daily Express found that Australia didn’t have a significant silk industry and the pearl fishing business was nowhere near as lucrative as Westwell’s supposed fortune. Furthermore, no record of anyone of that name in the pearl fishing enterprise could be found.

Journalists from the Manchester Evening News checked the passenger list for the Omrah. Nobody called Tunstall had been on the ship, let alone died and been buried at sea.[vii]

Further enquiry revealed that nobody – not even his own brother and sister – had ever seen or met Tunstall’s supposed first or second wife.

But if Tunstall had not sailed on the Omrah, then where was he?

Mad, Mad, Mad…Killed with Money

It turned out that Tunstall had been working as a labourer in Hollingwood, near Oldham. It was from near here that he had sent the telegrams to his brother and landlord. At his lodgings in Hollingwood, his landlady saw him write his name and address on an insurance card and then realised he was ‘the fortune man’ but decided not to say anything as he seemed comfortable there and wasn’t causing her any trouble.

One night in Hollingwood Tunstall went out for a herbal beer, and as he was walking down the street someone shouted, “lucky dog!” at him. He returned to his lodgings, presumably distressed that he had been recognised, though he told his landlady that there was a labourer from Bolton that had the same name as him that had been left a fortune. Tunstall told his hosts that he was going to a friend in Newcastle to find work. The journey involved changing trains at Todmorden, where he was found by PC Machlachlan dazed and confused on the banks of the Rochdale Canal.[viii]

A Todmorden journalist went to Vale Street police station to meet the famous Mr Tunstall and found him lying on a bench complaining of a pain in his head and saying that he had gone blind. ‘My eyes are gone,’ he said in a weary tone, and this seemed to be confirmed when the journalist put his fingers close to his face and got no reaction. Tunstall maintained his inheritance was true, and that he had gone to London with Harry Hart to sail to Australia but had no memory of what had happened. ‘I wish I had never had the money,’ he told the journalist. When asked directly why he hadn’t sailed to Australia, he replied ‘That’s what I want to know.’

Todmorden police had contacted Tunstall’s sister Sarah who arrived at this point. When she saw her brother, she let out a glad cry and ran to embrace him. She then shook him vigorously and told him he was coming home with her and talked of how worried they’d been after the telegrams about his death.

Tunstall began to weep on his sister’s shoulder. ‘That’s right, have a good cry, you’ll feel better. He has been like this many times,’ she then told the journalist. ‘And it does his eyes good to cry. I like to see him cry. It always does him good when he has trouble with his eyes.’[ix] It seems he had gone temporarily blind on previous occasions.

The last we hear of the mysterious Mr Tunstall is that he returned to Bolton with his sister, still blind and supposedly in a critical condition.

Epilogue

William Tunstall was a teller of tall tales. His Australian fortune. His heroic sea rescue. His serendipitous romance. The tragic death of his wife and child. His second wife and retinue of orphans. His apparent betrayal by the mysterious Mr Hart. His suspicious death and dramatic burial at sea… all were pure fiction. So, perhaps, was his seeming madness, loss of memory and blindness when he was discovered on the banks of the Rochdale Canal in Todmorden.

However, Tunstall’s story was believed by his sister and brother, by his friends at Bible class and by many others in and around Bolton. He had faked his death because of the stress and strain caused by all the public attention his fortune had brought him…

Perhaps Tunstall was what contemporary psychiatrists might call a pseudologue – that is someone suffering from Pseudologia Fantastica, the symptoms of which are a pathological compulsion to tell self-aggrandising lies in which the teller is always the hero, heroine or victim. In doing this they harvest attention and nurturing from those around them, perhaps out of a sense of emotional desperation.[x]

My own research on episodes like the Halifax Slasher, ghost hoaxes and fake abductions makes me think that pseudologues may be far more common than we believe.[xi]

In any case, I can’t find any subsequent accounts of the further adventures of William Tunstall in the newspaper archives, but I can’t help but think his imagination kept on spinning melodramatic narratives to anyone who would listen.

For more exciting but dubious tall tales, see below…

[i] ‘Windfall Story’, Manchester Evening News, 20 August 1913, p.4

[ii] ‘Bolton Labourer’s Big Windfall”, Lloyd’s Weekly News, 17 August 1913

[iii] ‘Sequel to Labourer’s £200,000 Windfall’, Staffordshire Sentinel, 19 August 1913, p.2; ‘Son’s 13 Year Sacrifice’, Daily Mirror, 19 August 1913, p.4

[iv] ‘Bolton Mystery’, Huddersfield Daily Examiner, 20 August 1913, p.4

[v] ‘Windfall Mystery’, Manchester Evening News, 19 August 1913, p.4

[vi] ‘Mystery of an Heir’s Death’, Daily Express, 19 August 1913, p.5

[vii] ‘Mystery of an Heir’s Death’, Daily Express, 19 August 1913, p.5; ‘Windfall Mystery’, Manchester Evening News, 19 August 1913, p.4

[viii] ‘Mysterious Mr Tunstall’, Manchester Evening News, 21 August 1913, p.6

[ix] ‘Bolton Romance’, Todmorden and District News, 22 August 1913, p.8

[x] Marc D. Feldman(2024) Playing Sick Routledge pp. 38-39

[xi] Robert Bartholomew and Paul Weatherhead (2024) Social Panics and Phantom Attackers, Palgrave Macmillan; Paul Weatherhead (2022) Weird Calderdale, Tom Bell Publishing